This is absurdly spot on, and you should read it. You don’t need to have read the book first; it includes all the context you need.

Category Archives: Books

“You saw something horrifying at the circus.”

How To Tell If You’re in a MFA Workshop Story is just a leetle close to my academic roots. It is, of course, hilarious.

Books of 2014, #20: Lock-in, by John Scalzi

That category, wherein I read nearly everything they write? Yeah, Scalzi’s in there. Just read it, for Christ’s sake. It’s a near-future murder mystery. What’s not to like?

Books of 2014, #19: Tigerman, by Nick Harkaway

Look, even if it’s not as much of a complete and perfect delight as The Gone Away World, how can you NOT love Harkaway’s language?

“If you just go out in the river and stand there long enough, you end up with a fish in your pangs and everyone thinks you’re a genius.”

Indeed. And then, there’s this:

“The last d ays are no less important than the others juyst because they are near to the end. Should we stop living today jsut because death is no longer a stranger?”

Tigerman is more or less straight fiction, and in that is a departure form the more SF/fantasy romp that was GAW, but it’s no less worth your time. The central story here is of a British functionary assigned to be the last official overseeing UK interests on a tiny (fictional) island that is, unfortunately, completely doomed. Things are actively falling apart, and the events of the story take place against a very real backdrop of impending doom, if not for the characters then for the island itself (hence that second quote).

Again, I’m running out of year here, or I’d say more, but the bottom line is that Harkaway is fast becoming the sort of writer I want to read all of.

Books of 2014, #18: The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett

Remember last year, when I read The Big Sleep? Yeah, more of the same — brilliant work, now seen as cliche, that was being invented at the time.

I’m terribly far behind on these posts, so the next few will be given the short shrift, but trust me when I say sampling the noir classics is worth your time.

Pulp SF has always been weirder than you can imagine

What’s more awesome: that a book called Crabs: The Human Sacrifice exist, or that it’s part of a series involving the plots and villainy of sentient crabs?

No, seriously. These are real.

As noted by one of the Tumblr commenters, I really, really want to know what sort of childhood beach trauma lies at the root of the author’s crab fear.

Books of 2014, #17: A World of Trouble, by Ben Winters

A World of Trouble concludes perhaps the most melancholy detective trilogy ever: as documented previously in the first volume (The Last Policeman, which was also the first book of 2013) and its followup (Countdown City, also last year), the world of Detective Hank Palace is about to come to an end. This is not a metaphor: a world-ending object is on a collision course with the earth, and its impact will probably kill everyone.

Instead of telling a big-hero story, or a big-science story, though, Winters does something completely novel: he focuses on the life of his protagonist and those around him as the world slowly comes apart over the course of the year. This final volume’s ending is no secret, given the setup, but getting there is where the story really lives.

It’s hard to discuss the third book in a trilogy without spoiling anything, so I won’t beyond saying the books are generally worth your time. I think my favorite is still the first one, which establishes Palace’s world, but the followups are rewarding in their own right even as the world gets bleaker and bleaker.

Books of 2014, #16: A Most Wanted Man, by John LeCarre

Finished 23 July

I’ll be brief: LeCarre is clearly not pleased with what passes for intelligence work in the post-9/11 world. Here, he paints a picture of barely functional agencies pursuing someone who is almost certainly NOT a terrorist. I won’t bother with the film, but Hoffman is perfect for the character he plays.

Books of 2014, #15: No Place to HIde, by Glenn Greenwald

(Finished July 30; I’m stupid behind on these posts.)

By now, everyone knows the name Edward Snowden, and what he did, and what he gave up to do what he did — and what challenges he may still face if the US government ever gets their hands on him. But do yourself a favor and read this book, because you really don’t know the whole story, and you really — still — have no idea how egregious the NSA’s behavior has been.

No Place to Hide is equal parts expose and thriller; the initial chapters detail how Greenwald was contacted by Snowden, and the tradecraft he had to learn in order to communicate with him. Snowden was very, very careful, and for good reason: as we’ve seen, his disclosures have been pretty explosive.

The second part of the story is Greenwald’s analysis of what’s been released so far: explaining the absurd, illegal, unconstitutional overreach of the surveillance in terms anyone can understand (and therefore be outraged by). These programs are ongoing, and are likely to remain issues in campaigns for some time to come, but we wouldn’t even know about them if it weren’t for Snowden.

The intelligence community is, obviously, totally bananas for all these programs, and why wouldn’t they be — it’s a spy’s wet dream to have access to this kind of data. But letting intelligence operatives decide where the line between “reasonable surveillance” and “criminally dangerous big brother shit” is a recipe for disaster.

Greenwald also gives us a pretty exhaustive history of surveillance, including a discussion of the effect this kind of “total information awareness” has on free (and not-so-free) societies. (Hint: it’s not good.)

Of course, the NSA isn’t acting in a vacuum here; there’s been a general failure of the press to act as a real check on government for a long, long time. Today, they so love their access that they’re completely unwilling to call out lies and bullshit. It’s much safer to regurgitate press releases without challenging anything. N.B. that it’s absolutely, unequivocally true that the Times knew about the wiretapping in 2004, before the election, and failed to tell anyone; something this explosive could have easily changed the election results.

But this is where we are: we have a powerful and craven intelligence (and law enforcement) community that views even dissent as unAmerican and dangerous even in the absence of actual wrongdoing or lawbreaking. This leads to a malignant expansion of state power, and cries out for someone to say something and at least begin the conversation in public about how much we’ll put up with. The press wasn’t doing it. Snowden and Greenwald have, and for that we all owe them a debt.

Hail to the King

Jack Kirby would’ve turned 97 last week. Courtesy of Hodgman, here are 170 of his two-page spreads. Enjoy.

Books of 2014, #14: Doctor Sleep, by Stephen King

Herein King succumbs to the decades-old temptation to answer the question “Whatever happened to Danny Torrence after the end of The Shining?”

Danny, as most everyone knows, escaped the Overlook Hotel with the help of Scatman Crothers and Olive Oyl, but as the book and film end (slightly differently) young Danny is still a child — and a child with some nontrivial baggage, too. He’s watched his father descend into madness and try to kill them before dying himself in a doomed and haunted hotel, and that’s completely aside from the other complicating factor: the Shining itself, which is what old Dick Hallorann called Danny’s special abilities. He’d seen that before, you see, which established way back then that Danny wasn’t alone in this gift.

So it’s a good question: what DOES happen to Danny? Doctor Sleep answers that for us, and I wish it were a better answer. By this I don’t mean that King dooms his hero — and disclosing that he doesn’t isn’t much of a spoiler, I don’t believe — but that the story detailing Danny’s later life isn’t as good as I wanted it to be. Everybody wants theirs to be Godfather II, but sometimes you end up with Godfather III instead.

The Stephen King who wrote The Shining is a very different man than the grandfatherly giant of American letters who penned Doctor Sleep, and it shows. The central horror of the earlier novel (as distinct from the Kubrick film) isn’t Jack Nicholson going nuts; it’s being inside the elder Torrence’s head as he loses his grip on reality, sobriety, and his own soul thanks to the evil and supernatural influences of the Overlook. Jack Torrence is a man with a drinking problem, and a man with other untreated issues (rage, impulse control, a chip on his shoulder), but not an irredeemable man, and certainly not a killer or true villain. On paper — as opposed to celluloid — Jack is as much a victim of the Overlook as anyone else; moreso, since he dies there while Dick, Wendy, and Danny escape. What I said in December stands, still: “The horror of the film is being trapped in a haunted hotel with a lunatic. The horror of the book is becoming the lunatic.”

This horror, we might guess, stems from the by-now well documented issues that King himself has had with alcohol and substance abuse, and his own horrors regarding mistreating his family and those around him. Jack takes the job at the Overlook precisely to put himself in a place where he CANNOT DRINK, remember; there’s no booze stored there during the offseason. Despite months of sobriety, he’s still trying to protect himself. And yet, despite these best intentions, the Overlook still claims him.

In Doctor Sleep, it’s no surprise to discover that Danny has inherited his father’s demons, but for a more tactical reason: the booze keeps the Shine away. Booze, a subtextual villain of The Shining, is out in front as a character in Sleep; when we meet Danny, he’s on his way to his own personal bottom well before he encounters the real bad guys of the story. That the arc also describes his recovery — complete with AA scenes and sponsors — is therefore not surprising.

But this isn’t the weak part of the story; King does this well, and like most of his stories he does a fine job of putting you in Danny’s skin as he wrestles with his alcoholism and the demands placed on him by the Shining. The weak part is the “by the numbers” tribe of King-baddies (“the True Knot”) haphazardly linked into the growing metastasizing continuity of the Greater King Universe. Yes, they’re awful. Yes, they torture and eat children. Yadda yadda yadda. It’s a little by the numbers, and I wanted more here. The earlier book’s strength stems from the fear that you could become the villain, under the right circumstances; here’s they’re just a supernatural Other to be battled and defeated, which is fundamentally less interesting than Danny’s own struggle with sobriety and the sort of “real life” he’s been avoiding for, at this point, decades.

The other weakness, and it’s one I’ve dinged King for previously, is length. You’d think they were paying him by the pound. I have no issue with a long story, but I want there to be enough story to justify the page count, and here (as with 11/22/63, though this is a much better book) there just isn’t. I mean, you rip through it quickly — King remains almost compulsively readable — but the story is thin when stretched out this far.

(By way of footnote, King also ends up repeating something that clanged loudly in the Kennedy book: (Highlight with mouse to read)Of course, when our hero succeeds in saving Kennedy, he returns home to an awful distopia because something something butterfly effect — a story trope that has been done absolutely TO DEATH in SF already, and which King should’ve stayed away from instead of telegraphing for hundreds of pages. Here, what ultimately helps Danny take down the bad guys — metahumans who feed on children who Shine — is the fucking measles. Herbie Wells called, Steve; he wants his deus ex machina back.)

Thug Notes just keeps getting more awesome

This week: At The Mountains of Madness, by H.P. Lovecraft.

Books of 2014, #13: Bark, by Lorrie Moore

I’ve been a fan of Moore’s stories for a long, long time, largely on the strength of this passage:

“The thing to remember about love affairs,” says Simone, “is that they are all like having raccoons in your chimney.”

“We have raccoons sometimes in our chimney,” explains Simone.

“And once we tried to smoke them out. We lit a fire, knowing they were there, but we hoped the smoke would cause them to scurry out the top and never come back. Instead, they caught on fire and came crashing down into our living room, all charred and in flames and running madly around until they dropped dead.” Simone swallows some wine. “Love affairs are like that,” she says. “They are all like that.” (“Dance in America”, from Birds of America)

Right? RIGHT? Moore’s writing has been heretofore dominated with a turn of phrase we might call Lorrian, and which I eat up with a spoon given half a chance. So it’s with disappointment that I report that her latest, Bark, is almost free of them. Only a few times did I feel I was really in the groove of the sort of writing that typified Who Will Run The Frog Hospital, for example. It’s still better than most, but not as solid as I was hoping.

Or, maybe she’s just doing something different, and I don’t care as much for the new thing; I suppose that’s possible. And she is not, of course, obliged to keep writing in the mode she did 20 years ago. (It’s fair to note that this is her first book of stories in 16 years, and that some of them I’d seen before in The New Yorker.)

The quips aren’t completely gone, though, so there’s some comfort in that:

- “Every family is a family of alligators.”

- “[Kentucky] is like Ireland, but with more horses and guns.”

and my favorite, which is this bit of dialog:

“You’re from what part of Chicago?”

“Well, just outside Chicago.”

“Where outside?”

“Michigan.”

My gripes about a lack of Lorrian turns of phrase notwithstanding, it’s still better work than most story writers. Moore’s world is one of disconnection and desperation that’s gone to flippancy (which is where the quips come from), and she still paints these pictures vividly, even when she drags the material too far into current events (Abu Ghraib is referenced, e.g.).

The sixth story, “Referential” sent me scribbling notes more than most; it reminded me of Richard Yates’ “No Pain Whatsoever”, a heartbreaking story about an estranged, cheating wife visiting her doomed husband in a TB ward while her lover waits in the car. Yates, though, didn’t play with language like Moore (or like Nabokov, who’s referenced in the story’s postscript).

From the NYT review:

Probably no writer since Nabokov has been as language-obsessed as Moore, but while Nabokov saw himself as an enchanter, a Prospero of words reveling in his power, Moore is a darker spirit, skeptical of language even as she makes it do tricks. “Mutilation was a language,” one character reflects when she sees her son’s cutting scars. “And vice versa.” She’s the most Beckettian of Nabokovians. Her characters banter and wisecrack their way through their largely mirthless lives in screwball-comedy style, but for them it’s a compulsive tic whose aim is sometimes self-protection (utterance that warns others off and forms a protective shell) and sometimes just to fill the void; the point is its pointlessness. “She had given up trying to determine his facetiousness level,” KC says of Dench, her relentlessly witty boyfriend. “She suspected it was all just habit and his true intent was unknown even to himself.” KC and Dench are the sort of people who note that a dried-out spider plant looks like “Bob Marley on chemo,” and that uterine cancer is “the silent killer. Especially in men.”

The eighth and final story, “Thank You for Having Me,” contains a final and bleak example of Moore’s characters’ not-quite-whistling past the graveyard — in this case, as with many, the source of ennui is advancing middle age: “Without weddings, there were only funerals. I had seen a soccer mom become a rhododendron with a plaque.”

Anyway, if you’re a fan of Moore, you’ll read it. If you’re interested in Moore, though, this probably isn’t the place to start.

Books of 2014, #12: Galveston, by Nic Pizzolato

Whoo-boy. For the record, I finished this book back on the 7th of JUNE, so my “behind-ness” is reaching truly amazing levels.

Pizzolato, of course, is the genius behind HBO’s True Detective, so when I realized he’d written a novel I had it on my Kindle in about 2 seconds.

It’s solid, though not as cleanly assembled as the (much more ambitious) True Detective. Our hero is dirtier than either of TD’s cops, and less given to philosophical ravings; our bad guys are less gothic and menacing. There’s an entire lack of backwoods murdering goons, and at no point do we encounter nubile young girls wearing antlers in their final repose. But it’s still solid, and there’s more than a little here that rhymes, thematically, with the HBO show; the biggest is the presence of a split narrative, taking place in two distinct timeframes but linked by a single character — who, inevitably, makes little men out of beer cans.

Definitely worth your time if you loved the show — significantly moreso than The King in Yellow.

Bill Hader reads more than you

The absolute best part of this is Paul being referred to as “M-Deezy”

Thug Notes takes on Dune.

When I am benevolent dictator, these will be everywhere

Biblio-mat dispenses a random book for $2.

“A woman who hates you is playing the pianoforte”

Thank God this isn’t real

I’d say that “Business Fantasy” is too manifestly ridiculous to really exist, but, well, if I’m honest I admit some demented sumbitch will probably write some just to be contrary.

yes i said yes i will Yes

Happy Bloomsday. This year marks the 110th.

Books of 2014, #11: Never Go Back, by Lee Child (Reacher #18)

Reacher finally makes it to Virginia, where madcap hilarity most decidedly does NOT ensue.

I mentioned before how Child had been building multi-book continuity related to Reacher’s desire to meet the current commander of his old MP unit. It was a new and welcome development, and probably mandatory given that, thus far, Reacher really hasn’t “developed” at all.

I’m therefore disappointed to report that Child more or less whiffs the finish. He gets there, solves the local mystery that inevitably involves his cross-country telephonic crush, and rides off into the sunset again. Even the somewhat shocking idea of Reacher being “reactivated” against his will, and therefore doing most of the book as an AWOL major, ends up being sort of meaningless.

Meh.

Books of 2014, #10: One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Honestly, it’s sort of surprising that I had never read this before. My literary reading has been, for decades, focussed primarily on postwar American works, with only occasional forays elsewhere, and that’s probably something I should address. On the other hand, there’s a lot of great stuff in that category, and there’s only time for so many books (especially this year, with my reading time severely curtailed by the new Less Chet is More Chet program).

Anyway, there it is: I’m new to Marquez. The book itself is hard to read in 2014 the same way it was read in 1967; the literary world has moved quite a bit since then, and this book is part of that movement. It’s obviously a titanic novel, rich in nuance and depth, but it’s also of a piece with its time, and it’s only in reading commentaries after I finished the book that I realized how many plot points in it were taken from actual historical events.

It’s also the sort of book that washes over you like an unrelenting wave; it’s clear that there are aspects to this work that will only become clear on repeated exposure, as with something like Ulysses or Infinite Jest.

Honestly, there’s just SO MUCH going on here, and it’s written so well, that it’s almost overwhelming; Harold Bloom said of it “My primary impression, in the act of rereading One Hundred Years of Solitude, is a kind of aesthetic battle fatigue, since every page is rammed full of life beyond the capacity of any single reader to absorb… There are no wasted sentences, no mere transitions, in this novel, and you must notice everything at the moment you read it”, and he’s not kidding. Marquez is harsh about some aspects of this world (like Faulkner’s treatment of Mississippi), but there’s also a love here that you don’t normally see in a Yoknapatawpha story. Surprisingly (post)modern techniques surface here, too — intertextuality, for sure, but that’s not the end of it. One gets a very “all of this has happened before, and all of this will happen again” feeling upon its completion.

Am I not saying enough? Well, it’s probably because even nearly a month later — I finished it in mid-May — I’m still turning it over in my head. But that’s a good thing.

Knee-jerk authoritarian ignorance in a southern school? UNPOSSIBLE!

Why are Cory Doctorow and his publisher sending 200 free books to Pensacola, Florida?

My publisher, Tor Books, is sending 200 free copies of the paperback of my novel Little Brother to Booker T Washington High School, because it’s the first school where any of my novels has been challenged by the school administration. Little Brother had been selected and approved as the school’s summer One School/One Book reading pick, and the school librarian Betsy Woolley had worked with Mary Kate Griffith from the English department to develop an excellent educational supplement for the students to use to launch their critical discussions in the fall. The whole project had been signed off on by the school administration and it was ready to go out to the students when the principal intervened and ordered them to change the title.

In an email conversation with Ms Griffith, the principal cited reviews that emphasized the book’s positive view of questioning authority, lauding “hacker culture”, and discussing sex and sexuality in passing. He mentioned that a parent had complained about profanity (there’s no profanity in the book, though there’s a reference to a swear word). In short, he made it clear that the book was being challenged because of its politics and its content.

Seriously, fuck that guy.

Books of 2014, #9: Chronic City, by Jonathan Lethem

(I’m so behind on these; I finished this book over a month ago. I’m also behind my 2013 pace significantly, but the biking is cutting into the reading, and the biking creates the “less Chet” phenomenon, so it is what it is.)

Lethem is an old favorite. I read As She Crawled Across The Table years ago, on the strength of an NPR review, and have followed his work since. He’s had great success, and has won literary awards in addition to a coveted MacArthur Fellowship. The resulting clout and the somewhat unfinished nature of Chonic City make me worry he’s crossed into the “un-editable” phase of his career. It’s the same idea as from this review of The Goldfinch back in February:

I’m no more privy to what went on behind the scenes in The Goldfinch’s journey from draft to publication than I am aware of the ins and outs of similar processes for Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot or Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue. But I know that all three of these novels (and there are many other examples) read as though their editor had been afraid to touch them, and had left early, baggy drafts unchanged.

Here, the problem isn’t so much that the manuscript is too long, but it absolutely is a bit cluttered when it comes to too-clever-by-half ideas seemingly wedged in on the strength of their own purported wit. That sounds super harsh, but I don’t mean it in that sense; Lethem is a very referential sort, peppering his work here with almost hypertextual links to pop culture artifacts that may or may not exist. It just feels like nobody told Lethem that he’d put in enough pepper already. That said, there’s a crazy amount of stuff going on here — nothing else has sent me to as many other learned reviews in years — so it’s not without reward by any means.

Chronic City is one of those love letters to Manhattan, but it’s a Manhattan that’s already gone it loves. Lethem misses the vibrant and artistic version from the 1980s, back when it was possible for weird artists and musicians to live on the island. I doubt they’ll be many such letters to the modern Manhattan of the 1%; Lethem’s bitter stand-in for the modern, wealthy-only Manhattan is a pristine apartment building restored and set aside for the city’s homeless dogs, about which more later.

Our notional hero, Chase Insteadman (the first of a host of improbable and Pynchonian names), is a former child actor (which is to say, he used to act; make of that what you will) engaged to Janice, an astronaut who is marooned on a space station with no obvious means of return due to “Chinese mines” in orbit. (Doubling down, we soon learn her health is imperiled as well.) Insteadman is an isolate: from Janice, obviously — she can write him, but for logistical reasons he cannot reply — but also from normal human discourse. Her letters, made public by NASA, have become nearly all he can remember about her. His residual income is enough to support him, which divorces him from everyday life, but it’s not enough to buy him entree into the world of wealth and privilege that he orbits as a sort of mascot (an object, an “extra man,” but not an actual participant). His isolation grows as the plot develops and we see other windows into his life.

Joining Insteadman early on is his sort-of friend and sort-of partner in crime, a quasi-employed writer and broadside artist named Perkus Tooth. Tooth is a Bangs-esque figure, hip without claiming hipness (think Hoffman’s Bangs in Almost Famous). Tooth is the source for much of the weirdness here; he has insane opinions on most everything (delightfully insisting that Brando is not dead, for example). He dresses like a throwback and lives in a rent-controlled apartment, thereby stuck in time in a fiscal sense as well as an aesthetic one.

The names just get weirder and weirder (not that I blame him): Laird Noteless is an artist specializing in enormous holes in the ground (no metaphor here!). Oona Laszlo is a ghostwriter, friend of Perkus’, and Chase’s secret lover. Strabo Blandiana is the acupuncturist to Chase and his wealthy pals. Another of Chase’s friends, Richard Abneg, is a former tenants’ right lawyer now working for the mayor undoing rent stabilization laws (chew on that); Abneg’s romantic partner is a Turkish heiress named Georgina Hawkmanaji that he always refers to as Hawkman.

(An excellent example of Lethem’s metaphorical seasoning: even with all this in play, he feels the need to have Abneg menaced by eagles; is it too literal to suggest he does so while hanging around with Turkeys?)

Much of the weirdness here comes from Tooth as he shows Chase into a sort of weird, parallel Manhattan. Tooth has become obsessed with objects called “chaldrons,” but the text gives no immediate hint that the word and the object are inventions of Lethem’s. The New York of Chronic City is full of references that might be real, that might just be something you’d never actually heard of instead of something Lethem has created (or, as in the case of Insteadman’s acting resume, a bit of both), and it gives the impression that the novel’s world is only a squint away from our own.

Lethem has also not been shy about inserting proxies for real world ideas so as to better lampoon them. For example, standing in for David Foster Wallace’s masterwork is a novel called “Obstinate Dust” by Ralph Warden Meeker; it becomes a minor MacGuffin in the story, but doing it once isn’t enough. Lethem drives the point home loudly when Oona mistakenly brings Tooth a copy of the also-fictional “Immaculate Rest,” a book of poems by Sterling Wilson Hobo instead (Tooth dismisses him as “a third-rate W. S. Merwin”). When called on it, she insists he should be thankful she didn’t return with “Adequate Lust,” which is apparently a how-to book.

These are throw-away lines to some people, I’m sure, but I have to believe most of Lethem’s audience is at least aware of David Foster Wallace, which places the whole riff too close to “look how clever I am” territory. This goes on and on; Henson’s creations wander through as the “Gnuppets,” named in a way that makes me wonder how much Lethem knows about free and open source software names. A proxy for Second Life/World of Warcraft shows up as the cheekily named “Yet Another World,” at first as a sidenote but later as a key point.

Tooth’s obsession with the chaldrons eventually leads our team to a weird sort of worship: they bid and bid on them when they surface on eBay, but with no intention of winning, even with access to Hawkman’s bankroll. Doing so drives them into an acquisitive frenzy even though they have no expectation they’ll ever actually acquire the object. The acquisition would establish a real connection, which can’t happen in a book obsessed with isolation. (It’d be hard to make these things more obviously MacGuffins, but that’s the way this book rolls.)

While all this is going on, Manhattan is menaced by an “escaped tiger” that is somehow never captured by the NYPD. It may be that the tiger is actually a renegade tunneling robot, under the control (?) of Abneg’s office and charged with damaging rent-controlled properties enough to force demotion, which would explain how a “tiger” could destroy buildings — but the whole tiger idea is blithely accepted, apparently, by most Manhattanites aside from Tooth. (As should be obvious, Lethem doesn’t miss the opportunity to lampshade the parallel between the “tiger’s” subterranean destruction and Noteless’ holes in the ground, though he’s more subtle about the “wild animal destroying village” angle that could’ve been drummed up here.)

Through all this, mourning of a certain kind of Manhattan predominates; it’s an isolating homesickness. That New York is Perkus Tooth, or at least Tooth represents the soul of it, back when artists could live in Manhattan. And that Manhattan is dead or dying. That he still lives there is an anomaly; Basquiat and Warhol and Reed are all gone, and we’re left with a fake version of the real city, now lost to time.

As the book draws closer to the end, revelations first hinted at and then explicitly stated make clear what drives Chase’s isolation:

Who could feel connection in a life like that?

I don’t mean to say the book doesn’t resolve; it does, and some of the ways in which it finally comes together are satisfying. Ultimately, though, it feels too loose, still full of too many of Lethem’s darlings he couldn’t bear to cut to create a more focussed and finished work. I’m glad I read this, and I enjoyed it, but still felt like more could’ve been done with the same material.

Here’s another couple reflections on the work you might enjoy:

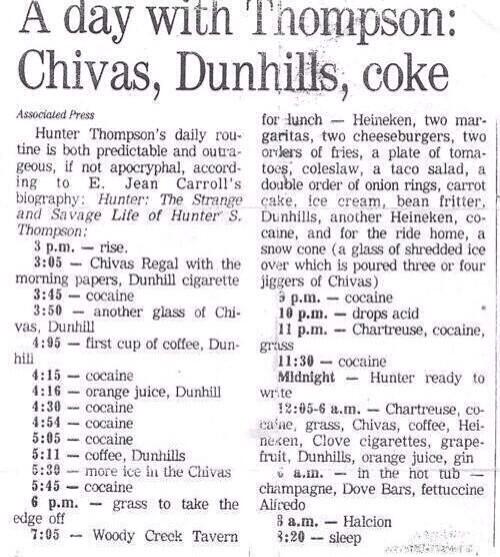

HOWTO: Work like Hunter

Books of 2014, #8: Pump Six and Other Stories, by Paolo Bacigalupi

I can say two things right off the bat about Paolo Bacigalupi.

First, he’s a solid writer with a great imagination. Unlike lots of science fiction, his stories are well-crafted and well-written for the most part. I enjoy his prose.

Second, Jesus FUCK what a downer this guy must be at parties. I kid; I have no actual idea. What I do know, though, is the bleak vision he has for the near-ish future. Bacigalupi’s stories take place generally in a world not far removed from our own, and extrapolate from current trends to produce a vision that’s disturbingly viable. A few of them in this collection take place in the world he created for his 2009 novel The Windup Girl; therein fossil fuels are exhausted or otherwise nonviable. Food energy and genetic engineering created the fallback position where springs and gene-hacked elephants are used to run machines. The world is dominated by the big “Calorie Companies” — ie, the agribusiness concerns that control the food supply with sterile GMO seeds and bio-engineered plagues created to destroy the naturally occurring foodstocks.

It’s not a happy place, to say the least, but it’s not his only disturbingly plausible future scenario. Pump Six comes with several other futures, and none of them are optimistic in the least (the title story posits a future that makes Idiocracy look upbeat, for example). This is not to say that you shouldn’t read the book (or Windup for that matter); they’re really well done. But you might need a unicorn chaser afterwards.

Books of 2014, #7: A Wanted Man, by Lee Child (Jack Reacher #17)

Yep, running out of Reacher. There is only one more in print. Another is schedule for publication in September.

This one’s not as much fun as either of the last couple. It starts out inventively enough by placing a hitchhiking Reacher in a car he quickly realizes contains two bad guys and an abducted woman despite their best attempts to conceal this fact — but, unfortunately, we end up in a sort of bog-standard one-man-vs-army-of-baddies endgame relatively quickly as Child wraps it up in a very by the numbers manner.

The most interesting aspect to this installment is probably Child’s continued experiments with interbook continuity. Like all such series, it usually helps to know what sort of adventures the protagonist has had before (and some are even explicit callbacks), but you could read them out of order without missing much — up to a point. Since 61 Hours (the 14th installment), though, Child has carried some aspects of Reacher’s own larger context through each story. This book-to-book story is its own narrative at this point.

For example, 61 Hours actually ends in one of those non-cliffhanger cliffhangers wherein his survival is nominally in question. Obviously, he’ll live; the only real mystery is how. We find out how in the next book, Worth Dying For (#15), wherein he carries a short-term injury earned in that escape that affects the way he handles the inevitable Deeply Corrupt Criminal Family Dominating Small Town. During his inevitable triumph, though, he has his nose broken.

The sixteenth book (The Affair) is a prequel, and tells the story of Reacher’s last case as an Army cop, and how he came to leave the service. However, when we rejoin the main continuity in A Wanted Man, his recently broken nose is a plot point, and he’s still headed to the destination he picked out during the final chapters of 61 Hours (after, of course, handling the situation with the abducted woman and the inevitable terrorists).

This sort of book-to-book continuity is new for Child; I’m choosing to see it as a positive development, though it remains to be seen if it’ll be more than window-dressing.

Books of 2014, #6: A Feast of Snakes, by Harry Crews

Harry Crews has been on my radar for a long time, but for some reason I never actually took the plunge. I was shocked this was still the case when he died last year, but it still took me until this month to read one of his books. I picked this one because, honestly, it was for sale in a local bookshop when David MacLean was in town reading from The Answer to the Riddle is Me. I felt bad about the fact that I’d pre-ordered MacLean’s book from Amazon, so I spent about $80 on other books while I was there for the reading, and so Crews found his way into my bag.

I can’t speak to Crews’ entire output, but Feast is something I might call “Faulknerian Modern.” If you read books like As I Lay Dying, or generally other books that touch on the Snopeses, it’s hard to miss the utter disdain and disgust Faulkner holds for most of his characters. Anse Bundren is a horrible, ignorant jackass of a man; of that there can be no question. It’s impossible not to read it and see a harsh critique of the South Faulkner knew well.

When I read Faulkner, that South is, temporally at least, far from me. I don’t react viscerally to the ignorance and general embrace of brutality, because I live in a more modern world, and his people don’t. I see them as awful, but they don’t make me HATE.

With Crews, though, it’s different. He’s doing much of the same thing here in Mystic, Georgia with Feast, except it’s set in 1975, and consequently resonates a great deal more. Frankly, I hate every one of these ignorant fucks, and by the end of the book sort of wished for a massive cataclysm to wipe Mystic off the map.

I”m not sure that Crews has the same sneering contempt for his characters that we see in some of Faulkner’s work, but it seems likely. Writers, like any other kind of intellectual, are generally unwelcome in the poor, rural south, and I’m sure Crews had some of the same scars that Faulkner had. At the same time, Crews includes a single learned character — the new boyfriend of a local girl come home from the University of Georgia — and treats him just as poorly, so there’s something in the rural south’s ignorant brutality that Crews seems to think as justified, too.

All that said, the book is solid. Despite my feelings about Joe Lon Mackey himself, I followed his story with the same horrified attention you’d give a train wreck (and, in that sense, was not disappointed). He’s the sort of person we have all seen: ignorant as fuck, but a star football player in a rural high school, so worshiped as a god until he graduated. College was never going to happen, so he is stuck in his backwater shithole town forever, endlessly revisiting his past while a profoundly shitty future stretches before him. No one we encounter is any less fucked up, or any less hopeless.

Should you read it? That, I’m not sure of. It’s harsh and brutal. There is endless violence. There is a brutal dogfighting subplot, the details of which make it clear Crews has been exposed to it in some detail. There is sexual assault. My takeaway was really just to be thankful that I do not have to live in a shithole like Mystic, or be around ignorant, ruined people like Joe Lon.

So that’s something.

Update: Apparently you don’t have to go all the way to Georgia for a ridiculous snake festival.

Books of 2014, #5: The King in Yellow, by Robert W. Chambers

There’s not really much to say here other than that Nic Pizzolatto and HBO have done more interesting things with the material than the original author.

I only heard about this because it turns out to be part of the mythos, if you will, for HBO’s True Detective; Amazon jumped on the bandwagon and made the Kindle edition of The King in Yellow free a few weeks back, and so I snagged it to read on vacation. (It’s still free, if you want to sample it.)

Honestly, it’s kind of bland, and not really worth your time. Only the first few stories even reference the titular King, and in those it’s generally in a very Lovecraftian thing-you-should-not-know sense. My advice: skip it.

There is nothing about this I do not love

Thug Notes is completely brilliant. The argument: stereotypical urban gentleman explains classic literature.

Books of 2014, #4: Use of Weapons, by Iain M. Banks (19 Feb)

Well, darn.

The first Culture book I read was the the awful Consider Phlebas a couple years ago. Honestly, it’s such crap that it nearly put me off the whole series. It wasn’t until last year that I bothered with the next volume of the series, Player of Games, largely due to the number of people I found who agreed that Phlebas was crap and that a better place to start was Games.

Ok, fine. Turns out, they were right; Games was a fun book. With Banks inconveniently promoted to the choir invisible, though, I didn’t want to run right into another Culture book, so I paced myself, and didn’t start the third book until this month. And now, having finished it, I think I’m done with Culture.

Weapons is a mess. Banks is trying an ambitious interleaved structure here, but it didn’t really work for me — largely because I never really gave a shit what happened, or had happened, to the protagonist. This is further reflected by the enormous gap between the last book and this one; by the end I was really finding this a slog.

It’s entirely possible Banks just isn’t for me.

More on Tartt’s *The Goldfinch*

This review is really, really spot-on. In particular:

I’m no more privy to what went on behind the scenes in The Goldfinch’s journey from draft to publication than I am aware of the ins and outs of similar processes for Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot or Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue. But I know that all three of these novels (and there are many other examples) read as though their editor had been afraid to touch them, and had left early, baggy drafts unchanged.

Telegraph Avenue is one of the few books I’ve simply given up on, which was really sad at the time given how much I’d loved Chabon’s other work.

Books of 2014, #3: The Answer to the Riddle is Me, by David Stuart MacLean (30 Jan)

So, here’s one for you.

Imagine suddenly “coming to,” standing in a train station — in India! — with no idea who you are, where you’re going, or why you’re there. You don’t know your name, where you’re from, who your parents or friends are, or even what your job is or why you’re in India.

I dunno about you, gentle Heathen folk, but that would freak me right the hell out. It’s horrifying and scary, but it’s the situation in which Fulbright scholar David MacLean found himself back in October of 2002. Local authorities initially took him for a shattered junkie, but the actual culprit turned out to be a then-commonly-prescribed antimalarial drug called Lariam.

What follows is MacLean’s harrowing and fascinating road to something like recovery. He doesn’t shirk the hard questions, either; much of our identity and sense of self is tied up with what we’ve done, and how we remember what we’ve done — but MacLean was robbed of this. On his trip home to Ohio to recuperate, he met his girlfriend, who was of course a stranger to him. He develops the ability to fake recollection, but all the while he’s really completely adrift and unconnected; he knows no one, and is vaguely threatened and alarmed that all these people seem to know him.

I’ve spoken to MacLean here in Houston, at a reading a few years ago. At that time, he had recovered much of his memory — but not all of it. He had no memory of his sister’s wedding, for example. But regaining what he did regain was a long road, and it begs the question of whether or not post-Lariam MacLean is the same person as pre-Lariam MacLean, and of what that sort of person-hood means. There’s no easy answer here.

It’s a fascinating read; I devoured it in a couple days, and would’ve read faster if I hadn’t been so busy with other things. You oughta read this book, for sure.

By the way, despite a series of these episodes, including suicides among US Special Forces, the drug is still widely available. However, the US military kept giving it to SF troops until last September. Worse, the military used mega-doses of it on all incoming detainees at Gitmo in an attempt to trigger psychological distress. (That’s not on the Wiki page, but it’s documented in MacLean’s book.)

Remember this drug, and make sure you don’t ever take it. The trade name (from Roche) is Lariam, but it’s also available as a generic under the name mefloquine. DANGER DANGER DANGER.

More on Command & Control

Schlosser has a short piece up at the New Yorker about the book that’s also worth your time.

Books of 2014, #2: Command and Control, by Eric Schlosser (27 Jan)

So, gentle Heathen, gather round, and let me give you a decades-delayed case of the nightmarish heebie jeebies.

My sense is that most of you are cold war kids, like Mrs Heathen and I. Our impressionable teen years coincided with a period of time when nuclear war was taken as almost a given; we were all fucked, but we just tried not to think about it.

Or, rather, we sort of WANTED to think about it, but then regretted doing so, which is the only way to explain the existence of such destructo porn as Threads and The Day After. Even lighter fare during the 80s, like Wargames, hinged on the obviously-imminent thread of nuclear armageddon. The sky is blue. Ice is cold. We’re all going to die. Inshallah.

Somehow, it didn’t happen. We’d like to tell ourselves a fairy tale at this late date that it never could’ve happened, or that the Russians were too afraid, and our leaders too wise, to ever let it happen, and that the collapse of the USSR was foretold and inevitable and all we had to do was wait out the clock, but none of those dogs will hunt. We stared oblivion in the face for the very best part of 40 years, and somehow lived to tell the tale.

And here’s the kicker, gentle heathen: we only made it out by the skin of our goddamn teeth, and with a heaping ton of good luck. If you thought nukes were scary when you were 16 and knew little about them, well, you got another thing coming: once you know how they work, how poorly they were secured and made safe, and how political tomfoolery kept them that way, they get a shitton more frightening.

Read on, if you dare.

Eric Schlosser‘s exhaustively researched new book Command and Control explores some hugely significant but generally neglected aspects of the nuclear weapons age: the fundamental safety (or lack thereof) of the American nuclear arsenal, and the development of nuclear strategy during that same period of time. The book tells these two stories interspersed with the actual story of a massive accident around a Titan II missile in Damascus, Arkansas in 1980.

What he finds — all of which is more or less indisputable, as it’s mostly matters of public record — is horrifying.

Start with this: There were hundreds and hundreds of accidents, big and small, involving live nuclear bombs. They were dropped on runways, set afire, accidentally blown up (but not detonated), and thrown into the sky by exploding missile fuel. Crashing bombers disgorged their world-ending payloads over American farms and Spanish villages. Entire missile systems were considered unreliable and downright dangerous by experts, but kept in service as bargaining chips with the Soviets. The Titan II, which was to carry our most destructive payload (the 9 megaton W-53 warhead, i.e. 400 times the yield of the Nagasaki bomb), was plagued by maintenance issues and a criminally dangerous propellant mix, but was kept in service for years even after an accident that could have easily obliterated Arkansas.

Despite what you may have been told, every single one of these accidents, in fact, could have resulted in what the experts refer to as a “criticality event.” Nuclear weapons hinge on a primary explosion that compresses a nuclear core. They’re packed with conventional explosives that must be triggered in a precise manner to produce the desired nuclear or thermonuclear explosion. However, exploding part of the conventional payload COULD very well set of a partial reaction.

Since most modern weapons have absurdly high yields, even less-than-optimum nuclear detonations would far exceed the power of any conventional weapon, and would come with the added extra bonus of lethal radioactive fallout — and, given our paranoia for most of the nuclear period, a very real chance that the accident would be interpreted as a strike or launch by one side or the other. Boom.

The complexity of the weapons themselves, and the limits of the command and control infrastructure, created a system where an accidental detonation of a thermonuclear device was not just possible but entirely likely. As analyst, Joint Chiefs advisor, and Stanford professor Scott Sagan put it, the fact that we never had an accidental detonation of a nuke is explained less by “good design than good fortune.”

Let that sink in.

Here’s the other punch line: because organizations like the Strategic Air Command were routinely flying around with live bombs (no, really; for a huge chunk of the pre-missile era, the SAC kept armed bombers in the air ready to go, carrying live nukes, just in case), and because live missiles were armed at all times during the Cold War, instances of heightened alert were actually MORE likely to produce an accident than more placid periods. It is profoundly easy to envision a world where the 30 days of tension during the Cuban Missile Crisis included an accidental detonation somewhere, or an accidental launch of forward-deployed tactical missiles from Turkey, and then where would we be?

Sagan again: “Nuclear weapons may well have made deliberate war less likely, but the complex and tightly coupled nuclear arsenal we have constructed has simultaneously made accidental war more likely.”

Yeah. It’s like that. Freaking out yet?

And, in fact, it’s even worse. Safety problems were routinely hidden from civilian officials, or even from top brass, by commanders in charge of weapon systems to avoid difficult questions, and to protect jobs and commands.

The policies and practices, especially in the early days of the arms race, were built on a freakish and naive faith in giant, monolithic control systems, and assumed many such systems would mesh with each other flawlessly. But it’s also inevitably true that such monolithic systems could not possibly survive what theorists referred to as a decapitation attack; we more or less assumed that the Soviets, in a surprise launch, could probably kill the President, most of the Cabinet, and most of the top military leadership. Where’s the central control then?

The Soviets, for their part, actually had an answer to this: they built a “doomsday” system, designed to fire their missiles automatically and without human intervention if it detected a nuclear detonation on Soviet soil. But they didn’t tell anyone about it, which sort of defeats the purpose.

The gamesmanship of nuclear strategy is also a huge part of the book, and it’s fascinating. Nuclear parity between the superpowers was “healthier” for everyone than an imbalance. If you think the other guy can wipe you off the map and leave you with nothing, you also think there’s nothing to stop him from doing so, so the idea of a sneak attack to even things up becomes more appealing. On the other hand, if you’re sure you could still wipe him out even if he hit you first, everybody is thought to be more polite.

This is a horrifying sort of mental calculus, but it was a huge part of our strategic thinking for more or less the entire missile age. Especially during the nontrivial portions of the arms race when we had a giant advantage, and both sides knew it.

(That’s another thing: the arms race was, for most of its run, a giant money and power grab by the military-industrial complex. There was no “bomber gap” in the 1960s, and the Soviets were NEVER really able to keep up with us in the missile age. They had a brief moment of public superiority with Sputnik, but after that it was all Yanks, all the time. Of course, when both sides have enough to kill everyone, keeping up is sort of pointless, and despite a missile gap in our favor the Soviets would have been able to turn most of Europe to glass in any exchange.)

But that’s all in the past now, right? WE don’t need to worry anymore, and we can sleep well again. Whew.

Well, not so much. Despite all our best efforts, nuclear nonproliferation is a dead letter. It turns out tech is easy to export, which is how countries in the emerging world have joined the nuclear club. What’s not easy to export, though, is an organizational culture that includes deep engineering know-how and safety controls.

The arms race between the US and the Soviets was, in nationalistic terms, largely abstract. I didn’t meet a Russian until after the Wall fell. I had no personal, familial, tribal, or regional beef with Russia; they were just the Other. This kept rhetoric and emotionalism largely out of the picture during our long period of detent. This isn’t the case, though, for at least one pair of new nuclear adversaries: India and Pakistan. The South Asian states have their missiles aimed at each other over Kashmir, and both are poster children for the “plenty of tech, but no engineering safety culture” problem I mentioned above.

Sleep well.

Books of 2014, #1: Something More Than Night, by Ian Tregillis (8 Jan)

Here we go again. Plus, I’m not even a month in, and I’m behind on the blogging.

I actually blame this book for the blogging part of that, because it was disheartening to start the year with something so disappointing and I kept putting off writing this entry as a consequence. Tregillis has taken a whole bunch of ideas and mixed them up here, and the result just doesn’t work. He’s got a Chandleresque narrator (for no discernable purpose, and boy HOWDY does that ever get tired) in a noir-ish mystery tale set among the angels in a near-future world where massive yet unexplored ecological changes have happened (but never mind those, because neither those changes nor the near-future setting matter at all to the plot).

Our other narrator — there are two — is more clear, and blessedly free of schtick, but she’s also so clearly the author/reader proxy that she struggles to be anything else. Her persona also tends to collapse under the weight of the info-dumps Tregillis imposes on her chapters, so as to bring us up to speed.

Tregillis is a bit too in love with his voice, I think. This can work for a writer and reader when the voice is consistent and confident; entire careers can be sustained by voice. (Some would say this describes Scalzi, but there’s more to his work by my lights, and being a voice-y writer isn’t a bad thing regardaless.) But Tregillis doesn’t have one of those voices; he comes off like a geek trying to impress with phrases and jokes that fall kind of flat. Sure, he gets some good bits in there — the phrase “like the offspring of an octopus and a Klein bottle” is nice, for example, but even it presupposes a level of geekery that will drive off readers outside the tribe. (Seriously, how many Heathen even know what a Klein bottle is?)

He also does that thing that prose writers do when they’re working in the truly fantastic (or what they think of as the truly fantastic) where they avoid direct physical descriptions because it’s all too far beyond human comprehension or whatever, and instead drop hints designed to shake you up without actually giving you anything substantive, like implying an angel has a variety of liplike things with which he could play a trumpet. It’s lazy writing, really, and annoys more than entertains. (Last year’s The Incrementalists was also guilty of this.)

Skip it.

Books of 2013: Stats Themselves

So, 53 in a year. Here’s how it broke down:

- The Kindle vs. Paper Smackdown

-

I read 24 on paper, leaving 29 to be consumed on Kindle and/or iPad. I admit I’m surprised by this, though only a little.

- The fiction/nonfiction/sci-fi & fantasy split

-

It was surprisingly even! 19 were fiction. 16 were nonfiction. 18 were science fiction/fantasy of some time. (Yes, the line between the first and last category is arbitrary and capricious. Deal with it.)

- Hey Chief Heathen! What’s the best nonfiction book you read last year?

-

I pick two: Going Clear, Lawrence Wright’s expose of Scientology, and David Foster Wallace’s epic collection of essays, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again.

- Hey Chief Heathen! I wanna read the best literary fiction you read last year!

-

Great idea! It’s Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead by a mile.

- Hey Chief Heathen! I’m a nerd like you! Hook me up with some great sci fi or fantasy!

-

You can’t go wrong with The Gone-Away World; also, pick up on Joe Hill. Horns is out in paperback, and will be a movie soon with Daniel Radcliffe and Juno Temple. There’s still time for you to get in ahead of the curve!

- Hey Chief Heathen! What book, regardless of other praise, shoud I avoid like the goddamn plague?

-

The fucking mess that is Gone Girl. As I said in April, it’s a dumb person’s idea about what smart person’s mystery might be.

That’s a wrap. We start over tomorrow.

Books of 2013: Juking the Stats

I decided, late in 2012, that it might be interesting or fun to track what I read in a year. I did this partly because I knew doing it “in public” like this would drive me to read more books — I had, in years past, let my novel consumption falter while I read more from the net and from periodicals or whatever — and partly because I knew I’d find it rewarding and memorable to take the time to write at least a little about each book as I finished it.

The goal I set was 50, and I made it with 53. In books, at least, I am apparently good at budgeting and forecasting.

What I didn’t realize was how often I’d find myself game-ifying the process and sort of “juking the stats” by avoiding bigger books in favor of slimmer works in order to keep my rate up. Partway through the year I added a column to the spreadsheet (because of course there’s a spreadsheet) that tracked whether my read rate was increasing or decreasing; obviously, I wanted that to show a positive rate, not a negative one.

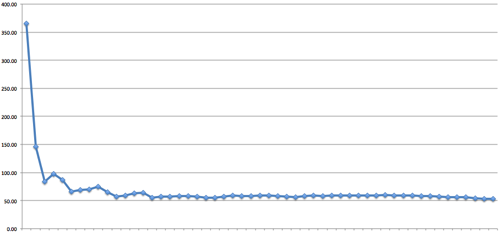

The curve over the year, expressed in “projected books per year at current rate”, looks like this:

Obviously, it starts high and then settles down. The real story is that for all my chatter about juking it up with Reacher books or whatever, the actual rate variance after the first quarter is relatively stable, as you can see.

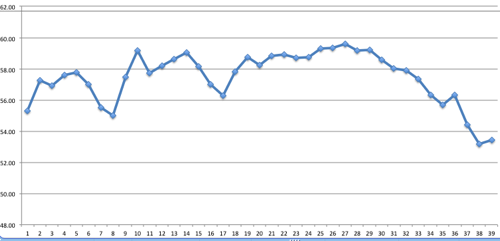

Part of that is compression based on the graph, but if we skip the books finished in January through March, it looks like this:

Pursuit of the goal had me shove aside some books I really want to read, though, like Eric Schlosser’s Command and Control and the ever-popular House of Leaves, both of which languish on my to-read shelf.

So for 2014, there is no goal. Or, rather, there IS a goal: read the books I want to read, and keep writing about them. Which I think is probably one I can easily meet.

Books of 2013, #53: The Affair, by Lee Child (Jack Reacher #16)

There was Christmas travel. Whaddayou want from me?

It took Child years to get there, but this one’s actually a prequel: It takes place a few months before Killing Floor, and tells the story of how Reacher came to leave the Army in the first place back in 1997.

Child’s gotten good at this, which is more or less what you expect with any series. If you look at the early books here, and compare with the early entries in Sue Grafton’s Kinsey books or Robert Parker’s Spenser books, you see commonalities: brisker, less fleshed out plots and characters, generally less interesting stories. Fast forward a few years, and the stories get some meat on their bones. (Hell, it even happened with the Potter books.)

The troublesome note is that there are only two more books currently available, though a 19th entry is scheduled for release next October.

Books of 2013, #52: Double Feature, by Owen King

“In which Chief Heathen accomplishes the King Trifecta”

Some time ago, I suggested that it might be fun to read books by Stephen King and his two novelist sons as part of this little experiment in documented bibliomania, and I’m happy to say I followed through — and then some, actually. From Joe Hill, I read Horns and NOS4A2; from the paterfamilias I read not just 11/22/63 but also The Shining; and, earlier this month, I finished Owen King’s debut novel, Double Feature.

Unlike his brother and father, King is working far afield from horror at all. His work is straight fiction with a literary bent, with no creepy-crawlies or dark forces at all. And while it’s easy to hear the elder King’s rhythms when reading one of Hill’s books, Owen’s language is his own. This is not to say there weren’t places where I felt like I was anticipating something weird happening, but it’s really hard to say if I’d have felt that way had I not known who wrote the book.

With all that said, I’ll also say it’s a good book. It’s not a great book, but it’s a good one, and it shows immense promise. There are some things that need tightening here, and the plot itself seems to meander and lose steam towards the end. There’s a clanger of an ending scene, too. All these bits are forgivable, though, for some of the language and scenes King assembles.

Central to the work is the relationship, however troubled, between our protagonist (young Sam Dolan) and his B-movie actor father, Booth. Booth hasn’t really been there for Sam, or for Sam’s mother. Booth isn’t without charm, and isn’t abusive, but his need to chase his own dreams left him ill-equipped to live a more conventional life when it was asked of him. Such is their rift that when, in college, Sam assembles the funds to produce his own independent movie, Booth isn’t even consulted.

The New York Times review of Double Feature is fair and kind, and is probably worth reading if only for this paragraph — which contains the only reference to King’s famous father, however oblique, to be found in the review:

The young Sam says he can’t stand his father, when the real problem is just dealing with him. It’s the great success of this novel that as Booth unwinds and slows just a little, we feel Sam becoming appreciative of the ham and the fraud. Booth is Wellesian, to be sure, but there are dashes of Falstaff, Micawber, Sterne’s Uncle Toby and the father in Geoffrey Wolff’s masterly memoir, “The Duke of Deception.” He has set-piece speeches and a collection of false noses. His talk is as heady as home brew. “Factually, we’re all dying,” he says, “all the time. From the moment of conception, we are dying.” Is that rhetoric or “King Lear” (a question that recalls Welles’s ability to improvise Shakespeare that neither the Bard nor anyone else had ever written)? You groan at the flights of fancy, but you want those wings for yourself, while seeing that a son would hardly dare to speak in the aftermath of so many grandiloquent speeches. If Owen King has a father (and he might), that man should be fit to burst with pride, and alarm, at this endearing monster.

(Emphasis added.)

There’s a lot to be happy about in this book, especially as a debut novel. It bounces around, timewise, and has some set pieces that don’t quite work, but more often than not it feels true. That’s as much as we can ask, and better than most work from more seasoned hands than the young Mr King. Let’s see what he does next.

Books of 2013, #51: The Gone-Away World, by Nick Harkaway

The Gone-Away World is, hands down, one of the most inventive and well-written and occasionally hilarious books this year — absolutely top ten if not top five. It’s a real gem of a book, full of absolutely hysterical turns of phrase (and bursts of satire worthy of Heller), but not at the expense of telling a pretty amazing story. Harkaway has built a hell of a world here — one that, at first, you don’t even recognize as being based on our own. I’ll absolutely be sampling more of his work in 2014.

To explain much of the plot is, I fear, to rob you of the experience of working it out on your own, so I’ll say little in that regard. It’s not a puzzle book, but it takes you a few chapters to get the gist, and the journey is worth it, so my advice it that you don’t even read the Wikipedia page.

What I can tell you about, again, is Harkaway’s glorious language. Here’s a few samples, just to taste:

Old Man Lubitsch holds up a single gloved hand, a sinner lost to apiarism, requesting indulgence.

and

[T]he tree of nonsense is watered with error, and from its branches swing the pumpkins of disaster.

and

We cruise along the main street, and it’s reasonably clear how the good folk here spend their time. The female half dances nude for the male half (with a statistical variation to account for less common orientations) or wrestles in a variety of convenience foodstuffs or performs in cinematic fantasies with simple, pithy titles. Some of the inhabitants engage in unmediated physical commerce of an ancient and simple sort. The porn shops of Matchingham observe a strict progression of obscenity, beginning with an almost fluffy eroticorium (catering either to tourists, if Matchingham ever had such a thing, or to the two or three women here who think of sex as a leisure activity), and moving from the modest HARD CORE! to the more self-aggrandising X-TREME HARD CORE!!! to various delights identified by jargon at least as impenetrable as Isaac Newton’s Second Law. The pale, as it were, beyond which one may not go, is a small shop with a faded handwritten sign and quite a lot of dust in the window. It stands just past an emporium sporting a neon outline of a woman swallowing the head of a Sucuri anaconda (the distinctive markings are surprisingly well rendered in lilac tubing) while being beaten by attendant cowboys with what appear to be starfish. It seems that the people of Matchingham have attained, with their limited resources, a jaded expertise in perversity I had assumed was found only in wealthy university towns. Even for this population of mining-town Caligulas, the little boutique to the left has gone too far with its simple sign: EXPLICIT EROTIC MOVIES—WITH A STORY!!!!

and, my personal favorite:

Unfucking is considerably more difficult than fucking. The Second Law of ther-mo-dynamics—because if you were thinking even for a minute that you are better educated than I am and therefore superior, Bumhole, you were mistaken—does not look with kindness upon unfucking. The level of fuckedness in a system always increases unless something acts on it from the outside. Worse yet, Bumhole, you do not own your own fuckedness. You do not appreciate the fullness of the fucking which has happened to you.

Look, if I have to know this, so do you

There is apparently such a thing as “Bigfoot porn,” but Amazon is doing what it can to stamp it out.

Books of 2013, #50: Worth Dying For, by Lee Child

Another business trip, and another Jack Reacher book. In this one, the 15th in the series, Child has his unstoppable former MP take on yet another in a series of isolated towns dominated by a local criminal clan. Frankly, it’s a testament to how (reasonably) fresh Child keeps his formula that I was actually shocked when this one turned out to hinge on human trafficking.

This one’s also of note because it picks up almost immediately after the conclusion of the prior book, which ended in something of a cliffhanger. I’m a little disappointed with how lightly Child treated that bit of information, but it was fun anyway.

Also amusing to me (and no one else) is it was an excerpt from Worth Dying For in an ad in the New Yorker (of all places) that started me on this series in 2010; I was at the Bethesda North Marriott in suburban DC at the time, attending an industry conference.

In an odd bit of synchronicity, I read most of Worth Dying For in the same hotel, attending the 2013 edition of the same conference.

When I started this series of posts in January, what I left unsaid was my actual reading goal. When I finished this book a month ago, I hit my mark: 50. The holidays have slowed me down, but I’ve read two more since then, and will probably bag at least one or two more before New Year’s Eve. Neat.

Books of 2013, #49: The Shining, by Stephen King

Yeah, I went there.

A friend of mine has been hosting a movie night in his new home since he moved in this summer; on one mid-November Monday, his choice was Kubrick’s now-iconic adaptation of King’s story of isolation, madness, and malevolent mountain hotels.

It is indeed a fine film; it’s aged well. At this point, we can really only ding it for the same thing that drove King himself to make his own film version some seventeen years later: Nobody was surprised when Jack Nicholson went homicidally nuts, which mutes what King has long said was the central horror of the book.

The film, inasmuch as it has a viewpoint character, focuses on Danny (and to a lesser extent, on Wendy). Jack is an external force, and one they fear due to his rage issues and his alcoholism. The family presents as one dominated by an abuser, not as one trying to escape its demons and start fresh. That Nicholson is sort of expected to be menacing and crazy drives the point home, which is why King went for someone decidedly more likable and normal in his “vanity” adaptation in 1997.

Remembering all this from articles in years past, I realized I’d never read King’s source novel as an adult, and as the movie night came right as I finished the aforementioned Goldfinch, I dove right in.

King is, fundamentally, correct. Kubrick made a great film, but King’s novel really is better. The novel switches perspective over the course of the story, giving us glimpses of life at the Overlook from Danny, from Wendy, from Hallorann (the Scatman character), and, crucially, from Jack himself. It’s Jack whose perspective is missing from the film, and it’s that perspective that helps make the book more horrifying than the film.

Jack is a broken person. His father was an alcoholic rage monster, and all his life he’s fought to keep those aspects of himself in check, with varying degrees of success. At the same time, his predicament — jobless, and therefore forced by economics to take the gig at the Overlook arranged for him by a wealthy friend — is not entirely his fault for reasons beyond the scope of this post. Sure, he contributed, but he’s a man both sinned against and sinning.

Key to the literary Torrence is his desire to be a good man to Wendy, and a good father to Danny. Danny is his world and his opportunity to do a better job than his old man did. (The portions told from Wendy’s point of view show her suffering from a parallel fear of becoming her mother, a domineering and nagging character in her life whose aid they cannot bring themselves to accept.)

As in the film, when we meet the Torrence family, Jack’s been sober for months. He’s doing well, but for their financial situation. He’s on a good track, personally, and would probably have been fine except for the Overlook itself, which sees the special capabilities present in Danny and wants them for itself. If it can push Jack into killing Danny in the hotel, it believes it can add Danny’s “shine” to the dangerous mix already present. The Overlook magnifies all their fears, pushing them to and then across the breaking point. (The idea that the Overlook is a sentient entity with real motivations, as opposed to just a haunted place, is something else Kubrick kind of glosses over.)

It’s worth noting that King has had his own well-documented battles with drugs and alcohol and anger. Jack wrestles with the demon that King himself was fighting, and the horror King ends up writing of is, once divorced from the supernatural forces of the hotel, the one that he feared most: losing control and harming his family. Turn that up to 11, add evil ghosts and an isolated hotel, and simmer.

The horror of the film is being trapped in a haunted hotel with a lunatic. The horror of the book is becoming the lunatic, which is much more personal, internal and, to me, horrifying.

Bonus Bit: James Bond at the Overlook

(The following is taken from an email I wrote my host after watching the film, because I am an obsessive bastard.)

The character Ullman, the hotel’s manager who hires Jack Torrence, was played by an actor named Barry Nelson. Nelson is of interest in Heathen circles (sadly) for his status as a 400-level Bond trivia answer: Nelson was the first man to play James Bond on film.

It’s widely believed that the Bond franchise got pretty weak sometime in Roger Moore’s tenure, and an obvious reason is that they were out of source material (the other big reason is that Bond was getting old; Moore was actually 3 years older than Connery, but never mind that). Nothing after Live and Let Die looks much like a Fleming book at all, because Eon Productions (the family concern who did all the Bond films) had already used them all.

Except one.

The literary Bond makes his debut in Casino Royale, but Eon didn’t adapt Casino until 2006; they began with an adaptation of Dr. No instead, which was the sixth of Fleming’s novels. Why did they wait 40+ years to adapt the first one while making blatantly subpar films like Die Another Day? One answer might be that Eon wasn’t first the party on Bond; prior the Eon’s Dr No in 1962, an American TV show called Climax! adapted Casino Royale, way back in 1954.

In this American TV version, our iconic British agent was reimagined as the American spy “Jimmy” Bond, played by Barry Nelson. Le Chiffre, now world famous as embodied by Mads Mikkelsen, was played by Peter Lorre.

But Wait There’s More!

As if that weren’t enough to put Eon off the book, Peter Sellers and David Niven would do a satirical adaptation of Casino Royale in 1967, as a spoof of the by-then enormously successful Eon productions. This presumably pushed a straight film of the book off the table until the pseudo-reboot in 2006 (though it seems weird that they didn’t try it with Brosnan).

Anyway: Barry Nelson was the first Bond. He made his screen debut in 1941’s Shadow of the Thin Man, and worked (85 credits worth!) until 1990. He died in ’07, at the age of 89.

This has been “Obsessive Chet’s Film Footnotes.” Enjoy your day, and Merry Christmas.

So what happens to Susan after Narnia?

This writer thinks she has quite a life, and I’m inclined to agree.

This is brilliant. Make time, even if you have only a passing interest in (or recollection of) Narnia.

(Frankly, that post single-handedly justifies both Tumblr and Twitter (which is where I found it) for pretty much ever.)

Books of 2013, #48: The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt

I would be substantially less annoyed by Donna Tartt‘s writing pace — at one novel per decade, Tartt makes George R. R. Martin look like Stephen King — if The Goldfinch hadn’t fallen so completely flat in its final third. Seriously, it just sort of comes to pieces.

It’s hard to explain or discuss much about this book without engaging in spoilers, but it’s probably okay to set the stage: our hero is a Theo Decker, and he’s a child when the book opens. He and his mother — his father has taken a powder — live in New York.

One day, his mother takes him to the museum, where he is thundersturck by the sight of a young girl being shepherded through the museum by an older relative. The museum, shockingly, becomes the target of a terrorist bomb. Separated at the time of the blast, our hero survives only to encounter a mortally wounded man — the same man who’d been escorting the young girl, who is nowhere to be seen. The dying man presses Theo to rescue the titular painting (a real one, by the 17th century painter Carel Fabritius), and so Theo becomes the guardian of a lost treasure — one presumed lost in the museum bombing. (Yes, real-world art losses are name-checked, so you get to feel clever if you know what happened to Rembrandt’s only seascape.)

What follows is a positively Dickensian Bildungsroman, at least for about 2/3 of the book. Who will care for Theo? Will it be his wealthy friend Andy’s family? Where is is his father, and will he turn up? What’s the story of the girl and the dying man? Where will all this go?

It’s the resolution of the last question, I’m sad to say, that Tartt kind of whiffs. We stay with Theo into adulthood, and the book holds together pretty well most of the way there, but the final sequence of events — which consume most of the last third of the book — aren’t quite right by my lights. There’s a weird shift in tone, and a strange sense of both too much and not enough. We reach an end, but it’s not really an end that feels right for the book. (I’m not alone in my reservations, as it turns out.)

So here I am. I loved The Secret History in 1992, and The Little Friend ten years later. Her sensibility agrees with me. I suppose I’ll buy her 2023 book at publication, too.

But disappointments are easier to weather when there’s more work to enjoy. Write like the wind, Ms Tartt.

Books of 2013, #47: The Incrementalists, by Steven Brust & Skyler White

First, let me say it’s goddamn amazing I didn’t see more jokes about Brust’s co-author’s name here, especially considering that The Incrementalists dropped right about the time Breaking Bad was wrapping up. Maybe it was just too obvious.

Anyway, this one’s short: I think, despite enjoying his own output as well as his public persona at talks, readings, and whatnot, that John Scalzi and I must have different tastes in SF. Scalzi loved this book, and even blurbed it, and so I figured it might be fun despite having read and been underwhelmed by the similarly-blurbed Ancillary Justice last month. The Incrementalists at least sounds interesting, given the premise: a secret cabal of sorta-immortals are dedicated to improving human society via tiny nudges here and there.

Unfortunately, instead of telling a story about how this happens, and what they’ve accomplished, what we get here is a weird sort of backstage, inside-baseball we’re-in-love-with-our-idea mess that I found to be a complete slog. There’s no accounting for taste, but I really thought the “big idea” (to steal a phrase) deserved a better story than we get in this book. Is there an existential threat to the group? Maybe, but since we don’t really know what they’ve done, or how, why should we care?

Anyway. This would not be the only book to disappoint me this fall, sadly.

Goddammit, Neil

That didn’t take long.

Fans of the original run of Sandman will remember how frequently issues were delayed, especially in the last third of the run. Comics are nominally monthly publications, but Sandman absolutely did not hew to this plan after a certain point; its 75 issues were spread over 84 months, with most of the disruption coming in 1994 and 1995.

Gaiman’s much-anticipated prequel, Sandman Overtures premiered last month. Issue 2 has already been pushed back until February for reasons undisclosed.

A sort of summary of several conversations I’ve had with Mrs Heathen

Books of 2013, #46: Mo Meta Blues, by Questlove

HOLY HELL DO YOU GOTTA READ THIS BOOK.

?uestlove‘s book Mo Meta Blues was already on my radar before Mike wrote about it a few weeks ago, but I’ll admit that having dinner with him (Mike, not Questlove) last week is what made me pick it up on the way out of Raleigh last Friday.