The billionaire founder of Home Depot has some advice for the Pope, which is just goddamn hilarious.

Yearly Archives: 2013

Books of 2013: Stats Themselves

So, 53 in a year. Here’s how it broke down:

- The Kindle vs. Paper Smackdown

-

I read 24 on paper, leaving 29 to be consumed on Kindle and/or iPad. I admit I’m surprised by this, though only a little.

- The fiction/nonfiction/sci-fi & fantasy split

-

It was surprisingly even! 19 were fiction. 16 were nonfiction. 18 were science fiction/fantasy of some time. (Yes, the line between the first and last category is arbitrary and capricious. Deal with it.)

- Hey Chief Heathen! What’s the best nonfiction book you read last year?

-

I pick two: Going Clear, Lawrence Wright’s expose of Scientology, and David Foster Wallace’s epic collection of essays, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again.

- Hey Chief Heathen! I wanna read the best literary fiction you read last year!

-

Great idea! It’s Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead by a mile.

- Hey Chief Heathen! I’m a nerd like you! Hook me up with some great sci fi or fantasy!

-

You can’t go wrong with The Gone-Away World; also, pick up on Joe Hill. Horns is out in paperback, and will be a movie soon with Daniel Radcliffe and Juno Temple. There’s still time for you to get in ahead of the curve!

- Hey Chief Heathen! What book, regardless of other praise, shoud I avoid like the goddamn plague?

-

The fucking mess that is Gone Girl. As I said in April, it’s a dumb person’s idea about what smart person’s mystery might be.

That’s a wrap. We start over tomorrow.

Books of 2013: Juking the Stats

I decided, late in 2012, that it might be interesting or fun to track what I read in a year. I did this partly because I knew doing it “in public” like this would drive me to read more books — I had, in years past, let my novel consumption falter while I read more from the net and from periodicals or whatever — and partly because I knew I’d find it rewarding and memorable to take the time to write at least a little about each book as I finished it.

The goal I set was 50, and I made it with 53. In books, at least, I am apparently good at budgeting and forecasting.

What I didn’t realize was how often I’d find myself game-ifying the process and sort of “juking the stats” by avoiding bigger books in favor of slimmer works in order to keep my rate up. Partway through the year I added a column to the spreadsheet (because of course there’s a spreadsheet) that tracked whether my read rate was increasing or decreasing; obviously, I wanted that to show a positive rate, not a negative one.

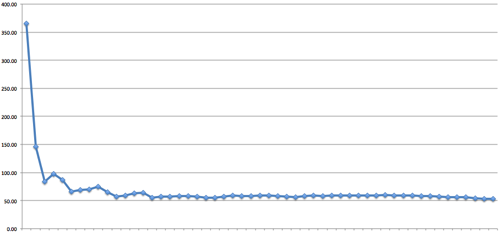

The curve over the year, expressed in “projected books per year at current rate”, looks like this:

Obviously, it starts high and then settles down. The real story is that for all my chatter about juking it up with Reacher books or whatever, the actual rate variance after the first quarter is relatively stable, as you can see.

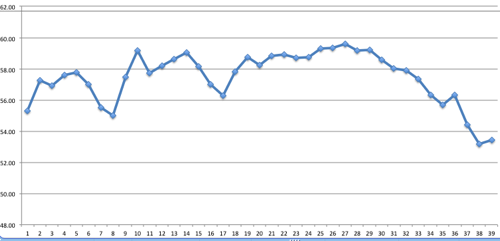

Part of that is compression based on the graph, but if we skip the books finished in January through March, it looks like this:

Pursuit of the goal had me shove aside some books I really want to read, though, like Eric Schlosser’s Command and Control and the ever-popular House of Leaves, both of which languish on my to-read shelf.

So for 2014, there is no goal. Or, rather, there IS a goal: read the books I want to read, and keep writing about them. Which I think is probably one I can easily meet.

Books of 2013, #53: The Affair, by Lee Child (Jack Reacher #16)

There was Christmas travel. Whaddayou want from me?

It took Child years to get there, but this one’s actually a prequel: It takes place a few months before Killing Floor, and tells the story of how Reacher came to leave the Army in the first place back in 1997.

Child’s gotten good at this, which is more or less what you expect with any series. If you look at the early books here, and compare with the early entries in Sue Grafton’s Kinsey books or Robert Parker’s Spenser books, you see commonalities: brisker, less fleshed out plots and characters, generally less interesting stories. Fast forward a few years, and the stories get some meat on their bones. (Hell, it even happened with the Potter books.)

The troublesome note is that there are only two more books currently available, though a 19th entry is scheduled for release next October.

Books of 2013, #52: Double Feature, by Owen King

“In which Chief Heathen accomplishes the King Trifecta”

Some time ago, I suggested that it might be fun to read books by Stephen King and his two novelist sons as part of this little experiment in documented bibliomania, and I’m happy to say I followed through — and then some, actually. From Joe Hill, I read Horns and NOS4A2; from the paterfamilias I read not just 11/22/63 but also The Shining; and, earlier this month, I finished Owen King’s debut novel, Double Feature.

Unlike his brother and father, King is working far afield from horror at all. His work is straight fiction with a literary bent, with no creepy-crawlies or dark forces at all. And while it’s easy to hear the elder King’s rhythms when reading one of Hill’s books, Owen’s language is his own. This is not to say there weren’t places where I felt like I was anticipating something weird happening, but it’s really hard to say if I’d have felt that way had I not known who wrote the book.

With all that said, I’ll also say it’s a good book. It’s not a great book, but it’s a good one, and it shows immense promise. There are some things that need tightening here, and the plot itself seems to meander and lose steam towards the end. There’s a clanger of an ending scene, too. All these bits are forgivable, though, for some of the language and scenes King assembles.

Central to the work is the relationship, however troubled, between our protagonist (young Sam Dolan) and his B-movie actor father, Booth. Booth hasn’t really been there for Sam, or for Sam’s mother. Booth isn’t without charm, and isn’t abusive, but his need to chase his own dreams left him ill-equipped to live a more conventional life when it was asked of him. Such is their rift that when, in college, Sam assembles the funds to produce his own independent movie, Booth isn’t even consulted.

The New York Times review of Double Feature is fair and kind, and is probably worth reading if only for this paragraph — which contains the only reference to King’s famous father, however oblique, to be found in the review:

The young Sam says he can’t stand his father, when the real problem is just dealing with him. It’s the great success of this novel that as Booth unwinds and slows just a little, we feel Sam becoming appreciative of the ham and the fraud. Booth is Wellesian, to be sure, but there are dashes of Falstaff, Micawber, Sterne’s Uncle Toby and the father in Geoffrey Wolff’s masterly memoir, “The Duke of Deception.” He has set-piece speeches and a collection of false noses. His talk is as heady as home brew. “Factually, we’re all dying,” he says, “all the time. From the moment of conception, we are dying.” Is that rhetoric or “King Lear” (a question that recalls Welles’s ability to improvise Shakespeare that neither the Bard nor anyone else had ever written)? You groan at the flights of fancy, but you want those wings for yourself, while seeing that a son would hardly dare to speak in the aftermath of so many grandiloquent speeches. If Owen King has a father (and he might), that man should be fit to burst with pride, and alarm, at this endearing monster.

(Emphasis added.)

There’s a lot to be happy about in this book, especially as a debut novel. It bounces around, timewise, and has some set pieces that don’t quite work, but more often than not it feels true. That’s as much as we can ask, and better than most work from more seasoned hands than the young Mr King. Let’s see what he does next.

Books of 2013, #51: The Gone-Away World, by Nick Harkaway

The Gone-Away World is, hands down, one of the most inventive and well-written and occasionally hilarious books this year — absolutely top ten if not top five. It’s a real gem of a book, full of absolutely hysterical turns of phrase (and bursts of satire worthy of Heller), but not at the expense of telling a pretty amazing story. Harkaway has built a hell of a world here — one that, at first, you don’t even recognize as being based on our own. I’ll absolutely be sampling more of his work in 2014.

To explain much of the plot is, I fear, to rob you of the experience of working it out on your own, so I’ll say little in that regard. It’s not a puzzle book, but it takes you a few chapters to get the gist, and the journey is worth it, so my advice it that you don’t even read the Wikipedia page.

What I can tell you about, again, is Harkaway’s glorious language. Here’s a few samples, just to taste:

Old Man Lubitsch holds up a single gloved hand, a sinner lost to apiarism, requesting indulgence.

and

[T]he tree of nonsense is watered with error, and from its branches swing the pumpkins of disaster.

and

We cruise along the main street, and it’s reasonably clear how the good folk here spend their time. The female half dances nude for the male half (with a statistical variation to account for less common orientations) or wrestles in a variety of convenience foodstuffs or performs in cinematic fantasies with simple, pithy titles. Some of the inhabitants engage in unmediated physical commerce of an ancient and simple sort. The porn shops of Matchingham observe a strict progression of obscenity, beginning with an almost fluffy eroticorium (catering either to tourists, if Matchingham ever had such a thing, or to the two or three women here who think of sex as a leisure activity), and moving from the modest HARD CORE! to the more self-aggrandising X-TREME HARD CORE!!! to various delights identified by jargon at least as impenetrable as Isaac Newton’s Second Law. The pale, as it were, beyond which one may not go, is a small shop with a faded handwritten sign and quite a lot of dust in the window. It stands just past an emporium sporting a neon outline of a woman swallowing the head of a Sucuri anaconda (the distinctive markings are surprisingly well rendered in lilac tubing) while being beaten by attendant cowboys with what appear to be starfish. It seems that the people of Matchingham have attained, with their limited resources, a jaded expertise in perversity I had assumed was found only in wealthy university towns. Even for this population of mining-town Caligulas, the little boutique to the left has gone too far with its simple sign: EXPLICIT EROTIC MOVIES—WITH A STORY!!!!

and, my personal favorite:

Unfucking is considerably more difficult than fucking. The Second Law of ther-mo-dynamics—because if you were thinking even for a minute that you are better educated than I am and therefore superior, Bumhole, you were mistaken—does not look with kindness upon unfucking. The level of fuckedness in a system always increases unless something acts on it from the outside. Worse yet, Bumhole, you do not own your own fuckedness. You do not appreciate the fullness of the fucking which has happened to you.

Dear US Customs at JFK

YES YES YES

Empirically speaking, the GOP is now 10% dumber than in 2009

Poll: Republican Belief in Evolution Has Plummeted.

As John Gruber notes, this means that in our two-party system, nearly half of one of the parties rejects settled science and believes that humans and other living things have existed in their present forms since the beginning of time.

Today in String Covers of Radiohead songs

Pyramid Song by Sybarite5 is delightful.

It’s marketing, but the footage is still great

This short GoPro film documents Kevin Richardson’s relationship with, among other things, wild lions in South Africa. They’re very happy to see him, on the order of the old Christian the Lion videos; they run up to him and want to snuggle. I’m sure his science is dodgy, but the video is still fantastic.

“She has this incredible ability to sing any Rolling Stones song as Julie Andrews.”

He’s not kidding.

Eddie Vedder and Jeanne Tripplehorn perform “Shattered” at a California benefit.

It is a small perfect wonderful thing.

You can tell it’s bullshit because Forrester is involved

The New Deal is the latest mumbo-jumbo middle-manager fantasy about software.

Let me save you some time, and paraphrase what it says:

We have no idea how software gets written, but we have the vague sense that software is hard, and we know lots of buzzwords.

(h/t: Rob.)

Empathy: Not a GOP value

In a recent documentary, Jim Buchy, a state legislator in Ohio, is on record as saying he wants there to be NO legal abortion in Ohio at all except to save a woman’s life.

The interviewer then asks him “Why do think a woman might want to have an abortion?”

Buchy’s response: “It’s a question I’ve never even thought about.”

It’s really not possible to make good policy when you refuse to even consider why the other side might disagree. Sure, you might consider the position and reject it, but to profess complete ignorance means you really haven’t looked into the issue at all.

We see this over and over with the GOP — on taxes, on social programs, on civil rights for gays, etc. It’s endemic. And it needs to stop.

The sheer BALLS required for this is amazing

Utility companies — who make a living by being a protected monopoly — are working very hard to impose fees on folks who install solar panels, i.e. who manage to escape their yoke.

SANTARAN CAROLS.

Commander Strax has an excellent Christmas message.

Bad news for Bill Donohue and other right-wing Catholics

Pope Francis enjoys an 88 percent approval rating among American Catholics.

WHAT IS THIS I DONT EVEN

In the early years of the last century, the U.S. Congress considered a bold and ingenious plan that would simultaneously solve two pressing problems — a national meat shortage and a growing ecological crisis. The plan was this: hippopotamus ranching.

Look, if I have to know this, so do you

There is apparently such a thing as “Bigfoot porn,” but Amazon is doing what it can to stamp it out.

Dept. of Regionalisms

I don’t usually go in for many online quizzes, but the New York Times’ dialect quiz placed me pretty much exactly, though I will admit I answered one question based on what we called it when I was growing up, not what I call it now. (I’m very conscious that the word we use for the road next to a highway in Texas is not the same word we used in Mississippi or Alabama; what do YOU call it?).

Books of 2013, #50: Worth Dying For, by Lee Child

Another business trip, and another Jack Reacher book. In this one, the 15th in the series, Child has his unstoppable former MP take on yet another in a series of isolated towns dominated by a local criminal clan. Frankly, it’s a testament to how (reasonably) fresh Child keeps his formula that I was actually shocked when this one turned out to hinge on human trafficking.

This one’s also of note because it picks up almost immediately after the conclusion of the prior book, which ended in something of a cliffhanger. I’m a little disappointed with how lightly Child treated that bit of information, but it was fun anyway.

Also amusing to me (and no one else) is it was an excerpt from Worth Dying For in an ad in the New Yorker (of all places) that started me on this series in 2010; I was at the Bethesda North Marriott in suburban DC at the time, attending an industry conference.

In an odd bit of synchronicity, I read most of Worth Dying For in the same hotel, attending the 2013 edition of the same conference.

When I started this series of posts in January, what I left unsaid was my actual reading goal. When I finished this book a month ago, I hit my mark: 50. The holidays have slowed me down, but I’ve read two more since then, and will probably bag at least one or two more before New Year’s Eve. Neat.

Books of 2013, #49: The Shining, by Stephen King

Yeah, I went there.

A friend of mine has been hosting a movie night in his new home since he moved in this summer; on one mid-November Monday, his choice was Kubrick’s now-iconic adaptation of King’s story of isolation, madness, and malevolent mountain hotels.

It is indeed a fine film; it’s aged well. At this point, we can really only ding it for the same thing that drove King himself to make his own film version some seventeen years later: Nobody was surprised when Jack Nicholson went homicidally nuts, which mutes what King has long said was the central horror of the book.

The film, inasmuch as it has a viewpoint character, focuses on Danny (and to a lesser extent, on Wendy). Jack is an external force, and one they fear due to his rage issues and his alcoholism. The family presents as one dominated by an abuser, not as one trying to escape its demons and start fresh. That Nicholson is sort of expected to be menacing and crazy drives the point home, which is why King went for someone decidedly more likable and normal in his “vanity” adaptation in 1997.

Remembering all this from articles in years past, I realized I’d never read King’s source novel as an adult, and as the movie night came right as I finished the aforementioned Goldfinch, I dove right in.

King is, fundamentally, correct. Kubrick made a great film, but King’s novel really is better. The novel switches perspective over the course of the story, giving us glimpses of life at the Overlook from Danny, from Wendy, from Hallorann (the Scatman character), and, crucially, from Jack himself. It’s Jack whose perspective is missing from the film, and it’s that perspective that helps make the book more horrifying than the film.

Jack is a broken person. His father was an alcoholic rage monster, and all his life he’s fought to keep those aspects of himself in check, with varying degrees of success. At the same time, his predicament — jobless, and therefore forced by economics to take the gig at the Overlook arranged for him by a wealthy friend — is not entirely his fault for reasons beyond the scope of this post. Sure, he contributed, but he’s a man both sinned against and sinning.

Key to the literary Torrence is his desire to be a good man to Wendy, and a good father to Danny. Danny is his world and his opportunity to do a better job than his old man did. (The portions told from Wendy’s point of view show her suffering from a parallel fear of becoming her mother, a domineering and nagging character in her life whose aid they cannot bring themselves to accept.)

As in the film, when we meet the Torrence family, Jack’s been sober for months. He’s doing well, but for their financial situation. He’s on a good track, personally, and would probably have been fine except for the Overlook itself, which sees the special capabilities present in Danny and wants them for itself. If it can push Jack into killing Danny in the hotel, it believes it can add Danny’s “shine” to the dangerous mix already present. The Overlook magnifies all their fears, pushing them to and then across the breaking point. (The idea that the Overlook is a sentient entity with real motivations, as opposed to just a haunted place, is something else Kubrick kind of glosses over.)

It’s worth noting that King has had his own well-documented battles with drugs and alcohol and anger. Jack wrestles with the demon that King himself was fighting, and the horror King ends up writing of is, once divorced from the supernatural forces of the hotel, the one that he feared most: losing control and harming his family. Turn that up to 11, add evil ghosts and an isolated hotel, and simmer.

The horror of the film is being trapped in a haunted hotel with a lunatic. The horror of the book is becoming the lunatic, which is much more personal, internal and, to me, horrifying.

Bonus Bit: James Bond at the Overlook

(The following is taken from an email I wrote my host after watching the film, because I am an obsessive bastard.)

The character Ullman, the hotel’s manager who hires Jack Torrence, was played by an actor named Barry Nelson. Nelson is of interest in Heathen circles (sadly) for his status as a 400-level Bond trivia answer: Nelson was the first man to play James Bond on film.

It’s widely believed that the Bond franchise got pretty weak sometime in Roger Moore’s tenure, and an obvious reason is that they were out of source material (the other big reason is that Bond was getting old; Moore was actually 3 years older than Connery, but never mind that). Nothing after Live and Let Die looks much like a Fleming book at all, because Eon Productions (the family concern who did all the Bond films) had already used them all.

Except one.

The literary Bond makes his debut in Casino Royale, but Eon didn’t adapt Casino until 2006; they began with an adaptation of Dr. No instead, which was the sixth of Fleming’s novels. Why did they wait 40+ years to adapt the first one while making blatantly subpar films like Die Another Day? One answer might be that Eon wasn’t first the party on Bond; prior the Eon’s Dr No in 1962, an American TV show called Climax! adapted Casino Royale, way back in 1954.

In this American TV version, our iconic British agent was reimagined as the American spy “Jimmy” Bond, played by Barry Nelson. Le Chiffre, now world famous as embodied by Mads Mikkelsen, was played by Peter Lorre.

But Wait There’s More!

As if that weren’t enough to put Eon off the book, Peter Sellers and David Niven would do a satirical adaptation of Casino Royale in 1967, as a spoof of the by-then enormously successful Eon productions. This presumably pushed a straight film of the book off the table until the pseudo-reboot in 2006 (though it seems weird that they didn’t try it with Brosnan).

Anyway: Barry Nelson was the first Bond. He made his screen debut in 1941’s Shadow of the Thin Man, and worked (85 credits worth!) until 1990. He died in ’07, at the age of 89.

This has been “Obsessive Chet’s Film Footnotes.” Enjoy your day, and Merry Christmas.

Microgravity Hangover

Turns out, if you spend enough time on ISS, you might need to unlearn some habits once you come home.

TSA: Still worthless. Still Ridiculous.

Go check and see what one photographer had to do to his lens blower to get it past security.

What morons.

Your Law Enforcement Elite At Work

Apparently, the FBI doesn’t know the difference between a MAC Address (which is the unique code assigned to a network interface, like your wifi adapter) and an Apple Macintosh (which is a type of computer).

You might not, either, but you’re not in charge of investigating computer-related crime.

I sort of love these

None of these will work, but they’re kind of brilliant anyway.

Dept. of Cheetahs

I’m trying to catch up with my RSS feeds this afternoon, and came across an story at IO9 including video of a cheetah and her dog pal frolicking in the snow.

My first reaction was that I should send it to my friend Linda the cheetah specialist in Cincinnati, but it turns out the snowy cheetah is the same one Linda introduced to Mrs Heathen and me last summer.

Heh. Small world.

In which Colbert speaks truth about American evangelical Christianity

It’s screencaps, but it’s worth your time.

Today in Alligator News

Yes, that was a by-God 4- or 5-foot specimen crawling across my mother-in-law’s back yard. ACHIEVEMENT UNLOCKED: THE REPTILIAN FLORIDIAN MENACE. It went into a nearby pond. The locals are alarming unalarmed.

Meanwhile, in Miami: “What the hell you mean I can’t swap this gator for some beer?“

Phrases I didn’t realize could be meaningful

This was, apparently, an actual literal thing. WHERE IS YOUR GOD NOW

This will end well, I’m sure

The Harris County GOP is suing the city and Mayor Parker over the fact that the city will now provide benefits to legally married same-sex spouses.

I’m sure this won’t hurt them AT ALL come election time, what with the city having elected a gay mayor over and over and whatnot.

Christ, these people are awful.

In case you’re still shoppping

25 Gifts for Writers seems pretty spot-on.

“I am leaving New York City because of all these goddamned wizards.”

Why I Am Leaving New York City has been open in my browser for months, but it still needs sharing.

Ex:

Last year my building went co-op after it was bought out by a representative of the Unseelie Court. They turned the super into a burning brand and replaced him with Robin Goodfellow, a large, hairy man with a tail who performs housework in exchange for a saucer of milk and a place in front of the fire. He is the son of a witch and the Devil and he still hasn’t fixed my radiator even though I put in a written request in September.

Now: Telepresence for your cats

PetCube is a remote-controllable device you can use to entertain your pets when you’re not home.

The future is weird.

And with that, RSA loses all credibility

Turns out, the pioneering security vendor has been in bed with the NSA for years.

This is incredibly shameful. I thank God for Edward Snowden, because otherwise this would’ve never come to light.

Boxing: Bankrupt

Just go read this long-form story about Manny Pacquiano. Boxing is a completely fucked up enterprise.

Well, at least the NSA has stopped some terrorists with this program, right?

Actually, turns out? Nope. There is no evidence that they’ve stopped even one attack despite running roughshod over the Bill of Rights for years.

Fuck. Them.

Apparently, being Swedish involves quite a lot of screaming

Why Jon Stewart is a goddamn treasure

Because he does things like this when his colleagues leave for greener pastures.

Jon Oliver — who famously took over the desk this summer — is getting his own show on HBO. Stewart is clearly proud and happy, and wanted to give him a bit of a send-off on-air. He also wanted it to be a surprise, though, so he wrote and rehearsed a completely false bit that required Oliver as the correspondent, and then broke character about a minute into it to shift into a really glorious sendoff compilation.

It seems pretty clear that Stewart’s a swell guy, and that the team at TDS have real affection for one another. It shows through the comedy, and probably fuels their success to no small degree.

Dept. of Things That Are In No Way Disconcerting

Only Duck Dynasty rednecks have the courage to warn us against the Shinto menace

The supposed patriarch of the bearded redneck millionaire clan has some charming points of view to share in an upcoming interview.

Grandpa Walton, Progressive Hero

The actor Will Geer was an icon in the 1970s because of his late-life success (and acclaim) playing Grandpa Walton, but (as with most folks in their 70s), he did quite a bit of living before that point.

Today, I found myself at his Wikipedia page. Go give it a read. Geer, a lifelong progressive, had quite a story — between organizing for labor, getting blacklisted, touring with folk singers in the 30s, introducing Woody Guthrie to Pete Seeger, etc. You know, normal stuff.

Turns out, he also inspired a character in a Richard Yates novel.

One Toke.

In 1971, somehow, the Lawrence Welk show featured a hokey, square performance of “One Toke Over The Line”; Welk himself referred to it as a “modern spiritual.”

Whiskey. Tango. Foxtrot.

The song is infinitely more famous for having been included in a particularly drug-soaked work of Gonzo journalism as well as the film adaptation (at 2:00 or so). There’s not another meaning for “toke.”

This must be what they meant when they talked about the “generation gap” back then. Still, you have to believe that someone at the Welk office knew just exactly what this song meant, and let the whole process happen as a goof.

Dept. of Excellent In Long-Running Late Night Gags

For many, many years, Paul Rudd has, very quietly, been running the best long-term late-night talk show gag I’ve ever heard of.

Dept. of Excellence in Advertising

I found this new Apple ad via Apple blogger John Gruber at Daring Fireball, who quite correctly invoked a certain early Mad Men scene in his post.

Enjoy.

Hey! Look! Insincere right wingers!

As it turns out, Hobby Lobby only hates contraception in the US. If it’s in China, and it’s mandatory, well, no problem!

Merry Christmas from the Doctor, Romana, and K9

The presence of Mary Tamm marks this as, most likely, Christmas 1978. The slightly more iconic and long-lasting regeneration of Romana was, of course, played by Lalla Ward after Tamm left the role in 1979.

Ward married Tom Baker towards the end of her run, but it didn’t last (ah, “showmance“). She’s been married to Richard Dawkins since 1992.

Tamm, sadly, is one of the few companions as yet promoted to the Choir Invisible. She died of cancer in 2012 at the age of 62.

HOWTO: Tell the Russians What You Think Of Their Bigotry

The White House has announced that the President, First Lady, and the Vice President will not be attending opening ceremonies for the Sochi Olympics, citing “travel schedules.”

Right.

Instead, President Obama is sending a delegation that includes, as its highest ranking member, a former (not current) Cabinet official. For context, this is the first opening ceremonies since 2000 that did not include at least someone of Cabinet rank.

Also included are two very prominent retired atheletes.

Representing the “diversity that is the US” will be tennis great and (Gay and Lesbian Sports Hall of Famer) Billie Jean King and figure skating medalist Brian Boitano.

It should escape no one that this comes the same week Bill O’Reilly pronounced Putin “one of us” in re: his stance on homosexuality.

Today in Linguistic Tomfoolery

If Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo amuses you, well, here’s something in German.

(It’s only this trip through the Buffalo… page that I notice the assertion that any number of repetitions of the word “buffalo,” terminated with a period, is a grammatically valid English sentence.)

More or less exactly what you’d expect from the NSA

They’d like to reform the First Amendment, to, you know, make sure stories about them are reported accurately.

End these fuckers and start over.